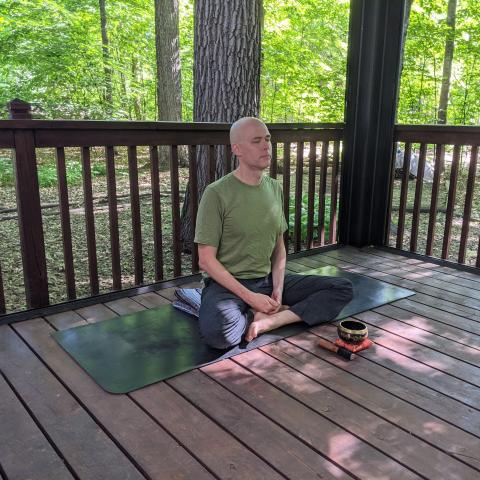

The Scene of the Incident

This morning I decided to teach my online Hatha Yoga class on our deck rather than inside our house like I usually do. After a long succession of hot and humid days, today has felt much more comfortable. And like my recent encounter with geese while teaching yoga at the Minnesota Arboretum, this class featured a visit from the local wildlife.

During the class I heard a lot of squirrels chasing each other around in our heavily wooded backyard, and then just before the final savassana I heard a loud noise from the gazebo roof above me. I thought the noise was the result of a large branch that fell from a tree, but then I realized it was a squirrel that had fallen from a tree. At first the squirrel seemed stunned, but then it got up and started walking toward me.

While I would like to report that the loud bang and the sudden sight of a squirrel a few feet away had little affect on me, that would not be accurate. I had been lying on my back in happy baby and I clumsily fell onto my side, slightly fearing for my life, while yelling something along the lines of "WHAT THE...!!" (the class was not being recorded, so I can't confirm what I actually said). One of the students in the class was nice enough to unmute herself and ask if I was okay.

The dazed feeling did not last long. I stood up and looked the squirrel straight in the eye. I would like to think that I was emitting a patently peaceful vibe which allowed the squirrel to feel comfortable enough to run away and get back to chasing other squirrels around in the trees.

Exploring Equanimity

Since my incident with the geese, and again with this squirrel, I have been contemplating the topic of equanimity. In the Pāli language, upekkhā is typically translated as "equanimity." In Sanskrit, the word is upekṣā. In lots of ancient texts, equanimity plays a key role in establishing a peaceful life:

- Upekkhā is the fourth of "four sublime states" (brahmavihārās) of Buddhism, yoga (Patanjali's Yoga Sutra 1.33), and elsewhere

- Upekkhā is the highest of the "seven factors of awakening" (satta bojjhaṅgā)

- Upekkhā is one of the "ten perfections" (paramī)

- Upekkhā is one of the "wholesome mental factors" (kusala citta)

The Sanskrit word samatva is likewise often translated as equanimity and in the Bhagavadgītā 2.48 is used as a definition of yoga (Patton 29; for other definitions of yoga, see Mallinson 17):

Abiding in yoga,

engage in actions!

Let go of clinging,

and let fulfilment

and frustration

be the same;

for it is said

yoga is equanimity.

Of course, beyond yoga, equanimity is praised in countless other religions (e.g., Judaism, Christianity, Islam), philosophies (e.g. Taoism, Stoicism), and elsewhere. Samuel Johnson defined equanimity as "evenness of mind, neither elated nor depressed." This seems mostly consistent with the translations of ancient texts and usage by modern commentators.

The Buddha described equanimity in this way:

And what is the faculty of equanimity? Neither pleasant nor unpleasant feeling, whether physical or mental. This is the faculty of equanimity.

In this context, the faculties of pleasure and happiness should be seen as pleasant feeling. The faculties of pain and sadness should be seen as painful feeling. The faculty of equanimity should be seen as neutral feeling.

Equanimity signals a lack of grasping, holding, craving, or revulsion. Upekkhā is sometimes confused with indifference, but there is no dullness about it. A cow probably doesn't care much if flies start bothering it, but the cow's relationship to those flies does not come from a place of wisdom. Equanimity is a cultivated skill.

I especially like Ajahn Amaro's phrase "diligent effortlessness" to describe equanimity. In its ideal state, equanimity does not take effort, but it doesn't just happen without determination. Like any other state, equanimity is something that can be clung to and thus not leading to a state of peacefulness. It's not a matter of wanting or trying to be equanimous. Equanimity is a deliberate state of action.

When the squirrel crash landed on the gazebo above me, just before our period of rest, I definitely felt shocked and momentarily scared. However, I also noticed how brief those feelings lasted. I acknowledged the unusual circumstances of the situation, and once the squirrel leaped off the deck, it was time to get back to our yoga practice. It's not difficult to image a Matthew from 15 or 20 years ago acting much differently, being far more affected and unable to relax.

I believe these everyday feelings of calm (whether real or imagined) that I experience more frequently come as a direct result of my daily yoga and meditation practices. Experiences like today only strengthen my resolve to continue practicing, learning, and sharing what I learn.

References

Bryant, Edwin F. The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali. New York: North Point Press, 2009.

Mallinson, James, and Mark Singleton. Roots of Yoga. Penguin, 2017.

Patton, Laurie L. The Bhagavad Gita. Penguin Classics, 2008.

Comments2

Yoga

very good blog about the sutras from yogic texts

Yoga Studio

amazing